Advances in the management of genitourinary melanomas

Introduction

Malignant melanomas originate from melanocytes of the neural crest and can be found in the cutaneous surfaces and mucosal membranes lining the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary (GU) tracts (1). While well known for producing pigmentation on the skin, the functions of melanocytes within the mucosa are not well understood, with some evidence for a role in antimicrobial and immunological activity (1). In contrast to the ultraviolet radiation-induced mutational progression of cutaneous melanocytes to melanoma, mucosal melanoma is hypothesized to arise from migration of melanoblasts to mucosal sites after undergoing an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (2).

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma far outweighs that of mucosal origin, which account for only 4% of all melanoma new diagnoses, although in specific populations the incidence of mucosal melanoma can be as high as 23% (3,4). While cutaneous melanoma is one of the most common malignancies in the United States with increasing yearly incidence, the incidence of mucosal melanoma continues to remain stable (1).

Molecular pathways

Whole genome sequencing of mucosal melanomas reveals a low mutational burden and lack of specific mutational patterns associated with ultraviolet radiation, cigarette smoking, or other known carcinogens (5). Many somatic mutations have been identified among cutaneous melanomas, most commonly in BRAF, represented in up to 62% of all cases, NRAS (10–28%) and NF1 (14%) (6-8). In contrast, approximately 55% of mucosal melanomas are wild-type for these oncogenes. Up to 39% will harbor c-KIT mutations, 12% NRAS mutations and 9–19% BRAF mutations (2,6,7,9-11). Molecular analysis of vulvar and vaginal melanomas has not shown significant variations with the exception of c-KIT mutations, which were found in 31% and 6% of cases, respectively (6). In two case reports of penile melanoma, Omholt et al. found that only 1 out of 5 patients had a BRAF mutation and Oxley et al. failed to identify any BRAFV600E mutations out of 12 patients evaluated (12,13). Evaluation of male GU melanomas found BRAF mutations in 50–60% of cutaneous lesions of the GU tract and c-KIT mutations in 15–20% of mucosal lesions of the GU tract (14).

Expression of the cell biomarkers programmed cell death receptor (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) have also been recognized as important prognostic biomarkers in cutaneous melanoma among other cancers, as downstream signaling from these cell wall receptors reduces the anti-tumor adaptive immune response (15). Cutaneous melanomas have been shown to express PD-L1 in approximately 35% of cases (16). Comparison with female GU melanomas found PD-L1 expression in vulvar (54%) and vaginal (25%) melanomas. Among the same group, it was uncommon for estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptor expression to occur even though developing from the female GU tract (6). There are no studies evaluating PD-1/PD-L1 status in male GU melanomas.

Analysis of the distinct genetic differences between cutaneous and GU melanomas highlights the potential for use of immunotherapy and targeted therapy, opening the door for treatment of systemic disease. Additional investigation is needed to fully define the biology of GU melanoma, as the rare nature of the disease precludes robust extrapolation of the genetic profile of these tumors. Larger studies of mutational analysis will improve the understanding of these subtypes as to whether it is correct to group them together in guiding systemic therapies.

Epidemiology

GU melanomas account for approximately 45% of mucosal melanomas, and can be further subdivided into female GU melanoma, including vulvar and vaginal melanomas; male GU melanomas, including penile and scrotal melanomas; and urothelial melanomas, including urethral, bladder, ureteral, and renal melanomas (17). Although most GU cases arise on mucosal surfaces, some develop on epidermal skin bearing surfaces such as the labia majora, penile shaft, and scrotum (18,19). A SEER database review published by Vyas et al. reviewed 817 cases from 1992–2012, noting a high disproportion of female GU melanomas accounting for 89% of cases compared to 6% in the male GU tract and 4% in the urinary tract. Incidence linearly increases with age and is highest in both men and women greater than 85 years old. A higher rate is also reported among non-Hispanic white woman and men (19).

Unlike the established course of cutaneous melanoma, the development of GU melanomas is less understood simply due to the rarity of occurrences (2). A family history of melanoma can be elicited from 10% of patients and when positive almost doubles the risk for future development of melanoma (20). In a study comparing cutaneous melanoma to those with genital and anorectal melanoma, family history of melanoma was a risk factor strongly associated with development in a mucosal site. In follow-up of these patients, 6% of patients diagnosed with mucosal melanoma subsequently developed cutaneous melanoma (21). With exception to melanomas of the urinary tract, GU melanoma is more prevalent and has worse outcomes among women. Mucosal GU melanomas (vulvar, vaginal, urothelial) have worse outcomes compared to GU melanomas associated with cutaneous surfaces (penile, scrotal), which may be selection-bias due to the later stage at time of diagnosis. In all groups, age, disease stage and lymph node involvement were the most important predictors of disease-specific survival (DSS) (22).

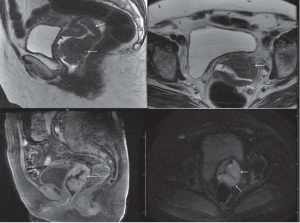

Female genitourinary melanoma

Among women, GU melanomas account for less than 5% of all vaginal malignancies and less than 1% of all melanomas. They most commonly present in the vulva (76%) followed by the vagina (19%) (18). Vulvar melanoma often present as asymmetrical black lesions with irregular borders, most frequently on the labia majora, labia minor, or clitoral hood (Figures 1,2). The most common presenting symptoms include pain, dyspareunia, dysuria, pruritus, bleeding, or a palpable mass (25). Vaginal melanoma may be diagnosed on routine gynecological physical exam, or present with abnormal vaginal bleeding (Figures 3,4). The median age of women with vulvar or vaginal melanoma at presentation is 66 years (IQR, 55–80 years) with 28–50% of women having regional or distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis (11,22,28). Clinical outcomes are poor with 5-year overall survival (OS) of 8–55% for vulvar melanomas and 15–27% for vaginal melanomas. In multivariate analysis, age greater than 65 years was associated with worse DSS (6,19,22,29,30). Tumor thickness, ulceration, and clinical amelanosis were also independent factors related to poor survival (25). Stage and lymph node status are significant, with 5-year DSS of 24% in node-positive patients compared to 68% for those who were node-negative (1).

Male genitourinary cutaneous melanoma

Cutaneous GU melanomas are those that arise on the outer foreskin, penile skin, or scrotum. The median age at presentation is 62 years (IQR, 50–77 years), and patients typically present with a pigmented lesion with irregular border or ulceration (22). Male GU melanomas account for 1% of all primary penile carcinomas, 65% of which will develop in the penis and 35% in the scrotum. Among penile melanomas, 28% of lesions will develop in the foreskin, and 9% on the penile shaft (17-19). At time of diagnosis, 37% will have regional or distant disease, and resulting 5-year DSS is reported at rates of 58–69% (17,19,22).

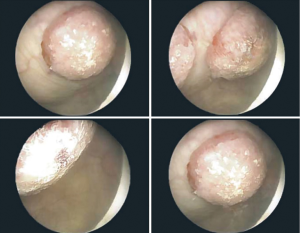

Male genitourinary mucosal melanoma

Penile mucosal melanomas arise on the glans, meatus, urethra, or internal foreskin. The median age at presentation is 62 years (IQR, 50–77 years), and patients typically present with concerns for a brown or black lesion with irregular border on the glans penis (Figures 5,6) (22). Later in the progression of disease, patients may experience obstruction of the urethra, ulceration, hematuria, dysuria and rarely, urinary fistula (14,17). More than half (55%) of penile melanomas arise in the glans penis and 8% in the urethral meatus (18). At time of diagnosis, 37–50% of men will have regional or distant disease. The prognosis is poor, with 5-year overall survival (OS) of 18–31% (13,22,33).

In one systematic review, 78 cases of glans melanomas were presented. As with other articles reporting on mucosal melanoma, associated risk factors or genetic predispositions were not found. Median depth of invasion at presentation was 2.6 mm (14). A non-uniform mixture of surgery combined with chemotherapy and radiotherapy was employed, with median OS of 28 months and 5-year OS of approximately 23% (14). In four small case series of penile mucosal melanomas, 5-year OS was reported as 20–80% with 11–62% of patients having lymph node metastases at the time of presentation (13,33-35). Age greater than 65 years, ulceration, Breslow depth greater than 3.5 mm, diameter greater than 15 mm, and lymph node involvement had significant adverse effects on prognosis (13,33,35).

Urinary tract mucosal melanoma

Urinary tract melanomas are more common in women (83%) than men (16%), possibly due to the higher concentration of melanocytes in the mucocutaneous tissue of the vulva (36). The median age at presentation is 75 years (IQR, 68–83 years) with 41% of patients presenting with regional or distant disease (22). In multivariate analysis, age was an important risk factor with patients 65 years or older carrying a worse prognosis. In contrast to other mucosal melanomas, there is no gender predilection for survival; overall prognosis is poor with 5-year DSS of 10–39% (14,19,22).

Primary melanoma of the urethra accounts for less than 1% of all melanomas and approximately 4% of all urethral cancers, most frequently located at the urethral meatus (49%), followed by the distal urethra (33%) (36). El-Safadi et al. identified 150 cases of primary malignant melanomas of the urethra, of which 60% of cases were women and 40% men, with mean age at presentation of 67 years (IQR, 28–96 years) (36). A systematic review reporting on 52 male patients with primary melanomas of the urethra found that ulceration of the lesion occurred in 64% of patients, leading to the most common presenting symptoms of pain and hematuria (14). Other clinical signs at presentation include dysuria, incontinence, and urinary obstruction (36).

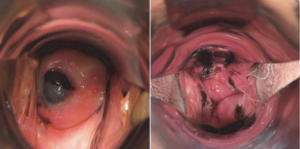

Primary melanomas of the bladder are rarer than the previously discussed subtypes, with only 31 cases reported. Bladder metastases from cutaneous melanomas are more common and as such, it is essential to first exclude primary melanomas that have metastasized to the bladder (37-42) (Figure 7). Criteria proposed by Ainsworth et al. to rule in a primary melanoma bladder lesion are: a detailed clinical history and complete dermatologic examination (including considering examination with a Wood’s Lamp) that shows no evidence of primary or regressed cutaneous melanomas, an ophthalmologic exam to exclude ocular melanoma, any recurrence pattern consistent with a source from a past primary tumor (i.e., multi-organ, multi-site recurrences, history of primary melanoma elsewhere), and the presence of atypical melanocytes at the tumor margins on microscopic examination (44).

There are only 5 reported cases of primary renal melanoma to date, and no confirmed cases of primary ureteral melanoma. Once again, renal and ureteral metastases from cutaneous melanomas are more common and thus should be excluded as explained in the paragraph above. Common symptoms at presentation include flank pain, hematuria, incontinence and urinary obstruction, which are nonspecific (45).

Natural progression of GU melanoma offers a paucity of early signs and symptoms of disease, with presentation in locations that are difficult to inspect on routine physical exam. As a result, diseases tend to be diagnosed at later stages. There is no standardized disease specific staging system in place for GU melanoma or any of its subtypes. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system can be applied, but there is little published literature evaluating its use (46). For patients with locally advanced disease, preoperative staging with computed tomography (CT) and/or positron-emission tomography (PET) and molecular testing for c-KIT mutation are recommended (47,48). Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has low morbidity, high accuracy, and has proven useful for cutaneous melanomas of certain thickness, therefore may be of use in the staging and treatment of GU melanomas (49). Pre-operative fine needle aspiration (FNA) of suspicious lymph nodes is infrequently mentioned in the literature but can be of value in planning operative management for those with regional nodal disease.

Staging and treatment of female genitourinary melanoma

Vulvar melanoma

Application of the AJCC TNM staging system for primary cutaneous melanomas has been shown to be the greatest predictor of recurrence-free survival in women with vulvar melanoma (Table 1). Breslow depth was the most important predictor of recurrence in stage 0–II patients (29). Patients diagnosed in early stages had significantly better 5-year DSS than those with stage III disease (51). Additionally, advanced age, ulceration, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, satellitosis and higher mitotic rate were all found to be associated with worse OS (50). In evaluation of applying the AJCC TNM staging system to vulvar melanoma, Nagarajan et al. found that it was only predictive of patient outcomes for tumors greater than 2 mm in thickness. Reclassification of stage with T1 defined as less than or equal to 2 mm with mitotic rate less than 2/mm2 and T2 defined as greater than 2 mm and/or mitotic rate greater than or equal to 2/mm2 provides improved prognostic value for OS and DSS (50).

Table 1

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| AJCC 8th edition (46) | |

| T-stage | |

| TX | Thickness cannot be determined |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | In situ disease |

| T1a | Thickness: <0.8 mm; ulceration: absent |

| T1b | Thickness: 0.8–1.0 mm; ulceration: present |

| T2a | Thickness: 1.1–2.0 mm; ulceration: absent |

| T2b | Thickness: 1.1–2.0 mm; ulceration: present |

| T3a | Thickness: 2.1–4.0 mm; ulceration: absent |

| T3b | Thickness: 2.1–4.0 mm; ulceration: present |

| T4a | Thickness: >4.0 mm; ulceration: absent |

| T4b | Thickness: >4.0 mm; ulceration: present |

| N-stage | |

| NX | Regional nodes not assessed |

| N0 | No regional metastases |

| N1 | Metastasis to 1 regional lymph node |

| N2 | Metastases to 2–3 regional lymph nodes, or satellitosis to nearby cutaneous structures, or in-transit disease |

| N3 | Metastases to 4 or more regional lymph nodes, matted regional lymph nodes, satellitosis to nearby cutaneous structures, or in-transit disease |

| M-stage | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1a | Metastasis to skin, subcutaneous tissue, distant lymph nodes |

| M1b | Metastasis to lungs |

| M1c | Metastasis to other organs, or metastasis to any distant site with elevated LDH |

| Nagarajan et al. (50) | |

| pT1 | ≤2.0 with mitotic rate <2/mm2 |

| pT2 | >2.0 and/or mitotic rate ≥2/mm2 |

Source: Adapted from referenced authors.

Historically, initial treatment of vulvar melanoma has been radical surgical resection with complete vulvectomy and bilateral inguinofemoral lymph node dissection irrespective of primary tumor characteristics (52). As aggressive resection led to significant morbidity without survival benefit and high local and distant recurrence rates, more conservative resection was evaluated with increasing emphasis on post-operative quality of life (47). Although conservative resection (wide local excision or partial vulvectomy with adequate margin) was found to increase the rate of local recurrence, several studies have demonstrated minimal differences in OS, disease free survival (DFS), or DSS compared to radical resection with or without inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (29,52-54). Other studies have found that most recurrences were distant or multi-focal rather than local (30,48). Excision with conservative margins of 1 cm for tumors that are 1 mm thick or less, and 2 cm for those 1–4 mm thick with a minimum 1 cm tumor-free deep margin have become the current standards (52,55) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Cancer type and stage | Extent of resection and margins | Nodal evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Vulvar (47) | ||

| Stage 0–IA | Wide local excision, 1 cm lateral margins down to fascia | Lymphatic mapping and SLNB, if positive disease upstaged to stage III |

| Stage IB–IIA | Wide local excision, 1–2 cm lateral margins down to fascia | Lymphatic mapping and SLNB, if positive disease upstaged to stage III |

| Stage IIB–IIC | Wide local excision, 2 cm lateral margins down to fascia | Lymphatic mapping and SLNB, if positive disease upstaged to stage III |

| Stage III (gross nodal disease) | Wide local excision of primary with 2 cm lateral margins down to fascia | FNA evaluation of clinically positive nodes. Unilateral lymphadenectomy if nodal disease is unilateral. Consider lymphatic mapping and SLNB to rule out bilateral drainage and microscopic nodal disease in the opposite inguinal nodal basin. Consider adjuvant systemic therapy and adjuvant radiation to bulky nodal disease and/or thick primary tumors |

| Stage IV | Wide local excision of primary tumor, tumor free lateral margin and deep margins to control primary tumor | Consider node dissection if grossly involved, and consider resection of oligometastatic isolated distant disease, however systemic therapy should be explored in stage IV patients, and surgery performed only if it is low morbidity and preserved function and/or palliative for symptoms. Radiation can also be considered for metastatic disease and /or palliation |

| Vaginal (56) | Wide local excision plus radiotherapy if possible | |

| Total exenteration | ||

| Urethral (57) | ||

| Stage A | Wide local excision with 2.5 cm margin if possible, total exenteration | No routine evaluation of regional nodes |

| Stage B–C | Wide local excision with 2.5 cm margin if possible, total exenteration | Lymphatic mapping and SLNB, consider complete lymphadenectomy if SLN is positive |

Source: Adapted from referenced authors with current authors’ recommendations. GU, genitourinary; SLN, sentinel lymph node; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Although it is accepted that nodal disease status is of important prognostic value, the role for routine use of nodal dissection or SLNB in patients with clinically negative regional lymph nodes is not well established. Sugiyama et al. reported an inverse relationship between survival and metastasis to the lymph node basins at the time of resection, with 5-year DSS of 24% among patients with nodal metastases compared to 68% among patients without nodal involvement (47). In evaluation of SLNB in vulvar or vaginal melanoma, Dhar et al. reported on 26 patients and concluded that SLNB carries a negative predictive value of 85% (58). Despite the relative lack of supportive evidence, SLNB is recommended as it allows for assessment of regional disease without significant morbidity, and if negative, may obviate the need for complete lymphadenectomy (29,55,59).

The role for neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment is unclear. Neoadjuvant treatment with chemoradiation has been used in unresectable vulvar melanoma as a bridge to surgical curative resection, or to reduce tumor burden allowing for a more conservative resection. In one case utilizing neoadjuvant therapy, the patient underwent resection after 50% reduction in size of the lesion, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, and remains disease free at 5 years (48). Another study evaluated 33 patients, 10 of which received adjuvant therapy with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or biological targeted therapy, and found no statistically significant difference in OS or recurrence free survival (RFS) between those treated with or without adjuvant therapy (48). In other series, adjuvant treatment with radiotherapy was associated longer DFS, increasing local control at 3 years from 57% with surgery alone to 71% with surgery plus radiotherapy; OS was not improved (48,53,60).

Vaginal melanoma

Application of the AJCC TNM staging system for primary cutaneous melanomas has also been shown to be the greatest predictor of recurrence-free survival in women with vaginal melanoma (Table 1). Patients diagnosed in early stages had significantly better 5-year DSS than those with stage III disease (51). Additionally, advanced age, ulceration, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, satellitosis and higher mitotic rate were all confirmed to be associated with worse OS (50). A caveat to AJCC TNM application of vaginal melanoma is that although Breslow depth has prognostic utility for the staging of early vaginal melanoma, survival outcomes have only been shown to be significant when comparing lesions less than 3 cm to those greater than 3 cm (10,52).

Vaginal lesions develop in the distal third of the vagina in 65% of patients. Improved OS has been demonstrated in patients treated with surgery when compared to those treated exclusively with chemoradiation (30). Therefore, recommended initial treatment of vaginal melanoma involves surgical resection with wide or radical local excision, complete vaginectomy, or pelvic exenteration (52). In retrospective review of 37 women with Stage I vaginal melanoma, the local recurrence rate was 22% and distant recurrence was 63% when initial treatment consisted of wide local excision (76% of patients), pelvic exenteration (14%), or radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy (10%) (30). Although conservative resection has been found by other authors to increase the rate of local recurrence, there are minimal differences in OS, DFS or DSS when compared to radical resection (29,48,52,53). Excision with conservative margins of 1 cm for tumors that are 1 mm thick or less, 2 cm for those 1–4 mm thick with a minimum 1 cm tumor-free deep margin are the current recommended standards (52,55) (Table 2). The role of SLNB previously discussed for vulvar melanoma can be applied to the treatment of vaginal disease.

Neoadjuvant treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy has been used in vaginal melanoma to reduce tumor burden allowing for more conservative resection. In two cases of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, one patient died within 3 months of resection. The other had partial response to neoadjuvant treatment, after which she underwent resection and adjuvant chemotherapy, and remained disease free at 2 years (48). In other series, adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy were associated with reduced local recurrence risk and longer DFS, increasing local control at 3 years from 57% with surgery alone to 71% with surgery plus radiotherapy, again without significant increase in OS (30,48,53,60).

Female urethral melanoma

Approximately 80% of female urethral melanomas develop in the urethral meatus and distal urethra. At presentation, the median depth of invasion is approximately 5–7 mm and 50–65% of patients will have regional or distant metastasis (14,36,61,62). In a systematic review, El-Safadi et al. reported an appropriate TNM classification in only 48 of 150 cases. Of the patients that were staged correctly, the AJCC TNM system was found to aptly predict prognosis according to depth of invasion (36). In addition to the AJCC 8 TNM staging system, investigators have used a similar staging system first proposed by RL Levine for urethral carcinoma in 1980 (63) (Table 3):

Table 3

| Stage | Criteria |

|---|---|

| A | Tumor within submucosa |

| B | Tumor infiltrating corpus spongiosum in men, or infiltrating periurethral muscle in women |

| C | Tumor extending beyond corpus spongiosum in me, or extending beyond periurethral muscle in women including into the vagina, bladder, labia, or clitoris |

| D | Metastasis to regional lymph nodes |

Source: Adapted from Levine, RL (63).

- Stage A—disease confined to the submucosa;

- Stage B—disease infiltrating the corpus spongiosum in men, periurethral muscle in women;

- Stage C—disease extending beyond the corpus spongiosum in men or beyond periurethral invasion in women including vagina, bladder, labia, or clitoris

- Stage D—metastasis to lymph nodes

Surgical excision for urethral melanomas has varied in extent, from local excision and partial or total urethrectomy, to radical procedures including cystourethrectomy with vaginectomy, vulvectomy, or anterior pelvic exenteration (64). DiMarco et al. reviewed 11 patients with melanoma of the distal urethra, finding that 8 had T3/stage C disease at time of initial resection. Out of 11 patients, 7 underwent partial urethrectomy of which 5 had local recurrence within the first year post-operatively. The remaining 4 who underwent radical extirpation, all had local and distant recurrence. OS for all patients was 27%. Despite these authors recommending radical urethrectomy to prevent high local recurrence rates, this study suggests that aggressive resection does not provide improved long-term outcomes and therefore may not be appropriate (17,62). However, these patients may still need radical surgery for disease in the proximal urethra depending on anatomic constraints. An optimal margin of resection has not been established as most studies have not provided specific resection details in their reports. Pooled data from systematic reviews suggests that a margin of 2.5 cm is adequate for stage A urethral melanoma (14,57).

Some authors have advocated complete inguinal lymphadenectomy for distal urethral lesions and pelvic lymphadenectomy for proximal lesions (65). In one study, patients with clinically negative regional lymph nodes underwent inguinofemoral lymph node dissection with no resulting difference in RFS or DSS (62). Although the survival benefit of lymph node evaluation is lacking, nodal staging with SLNB may have a role for planning adjuvant therapy but evidence supporting this practice not well established (52,57).

Staging and treatment of male genitourinary melanoma

In staging male GU melanoma, most investigators apply either the AJCC TNM system for penile cancer or use a 3-stage system proposed by Bracken and Diokno (14,66) (Table 4):

Table 4

| Stage | Criteria |

|---|---|

| I | Tumor confined to the penis |

| II | Metastasis to regional lymph nodes |

| III | Distal metastasis |

Source: Adapted from Bracken et al. (66).

- Stage I—disease confined to the penis;

- Stage II—metastasis to regional lymph nodes;

- Stage III—disseminated disease.

Clinical stage I with Breslow depth less than 3.5 mm presents with the best 5-year OS of 33–39%. For patients with locally advanced disease, preoperative staging with CT and/or PET and molecular testing for c-KIT mutation is recommended (32). As in treatment for vulvar melanoma, there has been a shift in the treatment of male GU melanomas from radical resection (total penectomy with bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy) to organ sparing surgery through wide local excision, urethrectomy, glans amputation, or partial penectomy. Organ sparing surgery and wide local excision provide effective local control for low stage disease (33-35) (Table 5).

Table 5

| Location | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Urethral (14,34) | |

| Fossa navicularis | Glans preserving wide local excision or partial penectomy (I,II) |

| Penile urethra (at or distal to peno-scrotal junction) | Consider wide local excision urethrectomy with partial penectomy (I) or total penectomy (II) |

| Bulbous urethra (proximal to peno-scrotal junction) | Consider wide local excision urethrectomy (I), or urethrectomy with prostatectomy, consider en bloc anterior exenteration with penectomy and total urethrectomy (II) |

| Penile (33,34,67) | |

| Foreskin | Circumcision |

| Glans | Amputation of glans or partial penectomy (I,II) |

| Glans and shaft | Partial penectomy if possible or radical penectomy (I,II) |

| Scrotal (67) | Wide local excision (I) |

| Regional lymph nodes (33,34) | |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy | SLNB if Breslow depth greater than 1.0mm or primary tumor ulceration |

| Completion lymphadenectomy | FNA positive or SLNB positive regional nodes |

Consider adjuvant systemic therapy to patients with positive nodes; consider adjuvant radiation to nodal basins involved with multiple nodes or bulky nodal disease. I, Resection with margins per AJCC 8 guidelines for cutaneous melanoma based on Breslow depth; II, emphasis should be placed on preservation of function as disease reaches high rate of morbidity and mortality regardless of resection. Source: Adapted from referenced authors with current authors’ recommendations. GU, genitourinary; SLN, sentinel lymph node; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; FNA, fine needle aspiration.

The median Breslow depth at presentation of male GU melanomas ranges from 2.6–4.9 mm (14,33,67). Only 11–17% patients presenting with stage I disease and low depth of invasion are reported to have inguinal metastasis, therefore routine inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy is not recommended (32,34). Routine SLNB at time of resection should be considered, particularly for those with suspicious nodes on imaging [ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)], Breslow depth greater than 1.0 mm, high mitotic rate, or ulceration (34,35,68,69). In patients with stage II or III disease, inguinofemoral dissection should be a palliative procedure for high volume disease only, as prognosis is poor with one systematic review reporting 2-year survival of 0% (32). As in treatment of female GU melanoma, pre-operative FNA of suspicious lymph nodes is infrequently mentioned in the literature, but can be of value in deciding operative management for those with suspected regional nodal disease.

Male genitourinary cutaneous melanoma

There is insufficient data regarding treatment of cutaneous lesions of the penis and scrotum to make evidence-based recommendations. However, most authors agree that staging and treatment according to the AJCC TNM guidelines for cutaneous melanoma of other locations is adequate (2,34,69,70). Further recommendations include treatment of penile foreskin melanomas with circumcision, and Mohs micrographic surgery, partial penectomy or radical penectomy if disease involves the shaft (34,35,69,71). Scrotal melanomas can be treated with wide local excision or hemi-scrotectomy without orchiectomy, or amputation (67).

Bittar et al. reviewed 127 cases of male genital melanoma, 38 of which qualified as cutaneous penile and scrotal melanoma and were also staged according to the AJCC TNM system. Of those, 18 were scrotal melanomas, 76% of which presented with tumor thickness greater than 2 mm and 44% had regional or distant metastasis at time of presentation. The majority were treated with organ-sparing surgery (89%) versus amputation (11%) (67). The same was true for cutaneous penile cases, with 70% receiving organ-sparing surgery. Local recurrence rates in scrotal cases were 18% after organ-sparing surgery, while neither of the 2 cases treated with amputation experienced local recurrence. None of the 7 foreskin melanomas had a local recurrence and 15% of the shaft lesions had a local recurrence. DSS and OS were not reported in this review (67). In a case series of 16 patients, 10 had penile and 6 had scrotal cutaneous melanoma. Of the penile cases, 7 had pathological T2 (0.76 to 1.5 mm Breslow depth) or less. Treatment of these patients with wide local excision or partial penectomy resulted in DSS of 86% at median follow-up of 39 months. Of the 6 patients with scrotal disease, all were treated with wide local excision without local recurrence and had DSS of 33% at median follow-up of 36 months. Breslow depth was not reported in these patients (34).

Male genitourinary mucosal melanoma

Surgical resection of male GU mucosal melanomas includes amputation of the glans if disease is limited to the glans alone, and partial or radical penectomy if disease involves the glans and shaft. Some authors have advocated for inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy for patients if clinically inguinal node positive, as this may offer a chance at curative resection (34,35,68,69).

A systematic review of 78 glans melanomas reported median depth of invasion of 2.6 mm at presentation. Across many studies, a non-uniform mixture of surgery combined with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy was employed for treatment, noting median survival of 28 months and 5-year OS of approximately 23%. All patients who remained alive at 5 years had presented with stage I disease and tumor depth less than 3.5 mm (14). Van Geel et al. summarized the treatment of 66 patients with penile mucosal melanoma, including the meatus and distal urethra. When compared to cutaneous melanoma outside of GU melanoma, localized primary mucosal penile melanoma had similar prognosis when adjusted for equivalent Breslow depth greater than 3 mm with 5-year OS of 43% (33). Interestingly, in 42% of patients initially treated with local excision, a positive margin was found on pathologic review leading to re-excision with local excision or partial penectomy. This finding warrants further research into appropriate margins of resection (33).

Male urethral melanoma

The majority of urethral melanomas develop in the urethral meatus and fossa navicularis, followed by the prostatic urethra, bulbous urethra, and penile urethra. At presentation, the median depth of invasion is approximately 5–7 mm and 50–65% of patients will have regional or distant metastasis (14,36,61,62). As in melanoma of the female urethra, authors have used both the AJCC TNM staging system as well as the Levine staging system for prognosis and operative planning (36,63) (Table 3).

Surgical excision for male urethral melanomas includes local excision, partial or total urethrectomy, and radical procedures (total penectomy, exenteration). Some authors have advocated for radical surgery of both proximal and distal lesions due to the high reported incidence of multifocal involvement at presentation and local recurrence rates of up to 60% after partial urethrectomy (14,57,61,72). Despite high local recurrence rates, aggressive resection does not provide improved long-term outcomes and therefore may not be indicated (17). When separated by staging groups, stage A patients have a much lower local recurrence rate (15–30%) after wide local excision, suggesting that wide local excision is sufficient (33,35). However, these patients may still need radical surgery for disease in the proximal urethra depending on anatomic constraints. An optimal margin of resection has not been established as most studies have not provided specific resection details in their reports. Pooled data from systematic reviews suggests that a margin of 2.5 cm is adequate for stage A urethral melanoma (14,57). Yet, as in primary cutaneous melanomas, increasingly radical resection does not result in better outcomes (14).

Some authors have advocated complete inguinal lymphadenectomy for distal urethral lesions and pelvic lymphadenectomy for lesions proximal to the penoscrotal junction (65). Lesions proximal to the membranous urethra drain into the pelvic lymph nodes and those distal to the penile urethra drain into the deep inguinal lymph nodes (73). Routine lymphadenectomy is not recommended for stage I/A urethral melanoma as there is high morbidity without survival benefit, but SLNB may have a role for nodal staging though it is not well established (57,74). For patients with confirmed inguinal lymph node metastases, some investigators advocate for ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy (33,35). Others suggest patients may be spared aggressive surgical therapy in lieu of adjuvant systemic treatment as resection has not been shown to improve long-term survival (61).

Staging and treatment of upper urinary tract melanoma

Bladder melanoma

Definitive staging of primary melanoma of the bladder, ureter, and kidney has not been addressed, likely due to the paucity of reported cases in the literature. A 2014 review performed by Venyo et al. reported 26 cases of primary bladder melanoma, citing general observations from each case report and concluding that visible hematuria is the most frequent presenting symptom and that prognosis depends on size, depth of invasion and presence of metastatic lesions. Nearly all reported cases have died of disease (37-42).

Surgical management of primary bladder melanomas includes transurethral resection, partial (wide local excision) or total cystectomy. There is at least one report of disease confined to the epithelium treated with transurethral resection without disease recurrence after 144 months (75). This case is clearly an outlier as most patients present late with invasion into the muscular wall. Conservative resection with adjuvant radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and interferon-alpha immunotherapy may have survival benefit (76). Despite aggressive treatment, locally advanced disease has poor prognosis, with no reports demonstrating survival longer than 3 years (17,77).

Ureteral and renal melanoma

There are five cases of primary renal melanoma reported to date. All cases were treated with nephrectomy with or without resection of the ureter, adrenal glands and associated lymphadenectomy. Two patients recurred with distant metastases within 1 year while 2 others remain disease-free at 22 and 27 months (45). Gakis et al. proposed that primary or metastatic renal and ureter melanomas should be treated by partial ureterectomy with an end-to-end anastomosis and wide margin, but if not possible then nephroureterectomy and regional lymphadenectomy. In the case of positive surgical margins, positive lymph nodes or tumor depth exceeding 1.5 mm, the authors recommend adjuvant systemic chemotherapy with dacarbazine in lieu of further resection. Unresectable disease can be treated with radiotherapy and systemic dacarbazine-based chemotherapy and stenting of the upper urinary tract (78). Macneil et al. reported on endoscopic resection of ureteral metastasis, citing metastasis to multiple sites shifting their intent to favoring functional outcome over definitive oncological resection (79).

Systemic treatment of genitourinary melanoma

Despite the unique tumor biology of mucosal melanomas, thus far systemic therapy for GU melanomas is based on experiences with primary cutaneous melanomas. Prior to 2011, dacarbazine and high dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) were the only available treatments for metastatic melanoma, neither of which demonstrated an improved OS. A randomized phase II trial in 189 patients with stage II or III (AJCC 8 TNM) mucosal melanoma showed that adjuvant treatment after complete resection with either high dose interferon-α2b (IFN) or temozolomide plus cisplatin chemotherapy resulted in improved outcomes compared with surgery alone. In subgroup analysis, 32 patients with GU melanoma exhibited median OS of 52 months with adjuvant temozolomide plus cisplatin and 41 months with adjuvant IFN (Table 6) (83). Postow et al. evaluated ipilimumab for mucosal melanomas, with a reported median OS of 6.4 months for metastatic or unresectable disease (89).

Table 6

| Author | Drug | No. of patients (n) | Median objective response rate (%) | Median overall survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoushtari et al. (80) | Pembrolizumab | 40 | 23 | Not reported |

| Nivolumab | 20 | 23 | Not reported | |

| D’Angelo et al. (81) | Nivolumab + ipilimumab | 35 | 37.1 | Not reported |

| Nivolumab | 86 | 23.3 | Not reported | |

| Ipilimumab | 36 | 8.3 | Not reported | |

| Yi et al. (82) | Dacarbazine/temozolomide | 95 | 26.3 | 12.1 |

| Lian et al. (83) | Cisplatin/temozolomide | 32 | Not reported | 51.8 |

| Kim et al. (84) (anorectal primary melanoma only) | Interleukin-2 | 8 | 44 | 12.2 |

| Harting et al. (85) | Interleukin-2 | 11 | 36 | 10 |

| Carvajal et al. (86) | Imatinib | 28 | 16 | 11.6 |

| Guo et al. (87) | Imatinib | 43 | 41.9 | 15 |

| Hodi et al. (88) | Imatinib | 24 | 29 | 12.5 |

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have also been applied to GU melanomas due to known mutations in c-KIT. A phase II trial demonstrated overall response rate (ORR) of 23% and median OS of 14 months after imatinib treatment (87). A phase II trial of the tyrosine kinase-inhibitor nilotinib had similar results (ORR of 26%, median OS 18 months) (90).

The anti-PD-1 antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab may have an important role for the treatment of female GU melanomas due to the high expression of PD-1/PD-L1 in vulvar and vaginal melanomas. Shoushtari et al. reported ORR of 23% to PD-1 blockade, regardless of age, mucosal sub-site, metastases, or prior therapy (80). Higher response rates were seen in combination with CTLA-4 inhibition, with ORR of 37% (81). Incidence of severe adverse events was 8% for nivolumab monotherapy and 40% for combination therapy (81).

Unfortunately, the low incidence of GU melanoma and heterogeneity of molecular expression makes it difficult to study with prospective trials. There are several ongoing clinical trials evaluating all mucosal melanomas. The SALVO trial (NCT03241186) is investigating combination ipilimumab and nivolumab after resection of mucosal melanoma (91). Another trial (NCT03986515) is investigating a novel anti-PD-1 antibody camrelizumab (SHR-1210, Jiangsu HengRui Medicine Corporation, Jiangsu, China) plus apatinib, an oral small molecule VEGF-inhibitor, in patients who progress after chemotherapy (92). Finally, the PIANO trial (NCT02071940) is investigating the KIT-inhibitor pexidartinib (PLX3397, Plexxikon Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA) in advanced KIT-mutated acral and mucosal melanomas (93). The results of these trials are eagerly awaited.

Conclusions

There is a paucity of literature guiding the management of primary GU melanomas. There are myriad presentations with different disease behavior based on anatomic location. The lack of published literature creates a challenging environment for development of staging and treatment strategies, which have been inconsistent since the first reported case. For an unknown reason, fine needle aspiration was very rarely discussed or employed for the evaluation of suspicious lymph nodes. This minimally invasive technique should be added to the repertoire of a surgeon’s pre-operative workup, possibly sparing patients the added morbidity of lymph node dissection. Treatment is challenging as diagnosis is typically made at an advanced stage, targetable activating mutations are infrequent and response to immunotherapy is not robust. The results of ongoing clinical trials will contribute much needed data toward the understanding of this rare disease. Future directions of care should stress the importance of detailed systematic reporting of each case, focus on creating a standardized system of staging and treatment and evaluate the application of new developments in genetic analysis and drug development.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, AME Medical Journal for the series “Rare Genitourinary Malignancies”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/amj.2019.11.03). The series “Rare Genitourinary Malignancies” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. Dr. Spiess served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid Associate Editor-in-Chief of AME Medical Journal from Sep 2017 to Feb 2020. JSZ has advisory board relationships withMerck and Array. He is a member of the speaker’s bureau for Array. He also receives research funding from Amgen, Delcath Systems, Philogen, Provectus and Novartis. He consults for Amgen, Delcath Systems and Philogen. He is also a member of the speaker’s bureau for Amgen and SunPharma. PES serves as vice chair for the NCCN panel for bladder and penile cancer. He also serves as an author for UpToDate.com. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P, et al. Primary mucosal melanomas: A comprehensive review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2012;5:739-53. [PubMed]

- Tacastacas JD, Bray J, Cohen YK, et al. Update on primary mucosal melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:366-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yde SS, Sjoegren P, Heje M, et al. Mucosal melanoma: A literature review. Curr Oncol Rep 2018;20:28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chi Z, Li S, Sheng X, et al. Clinical presentation, histology, and prognoses of malignant melanoma in ethnic chinese: A study of 522 consecutive cases. BMC Cancer 2011;11:85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furney SJ, Turajlic S, Stamp G, et al. Genome sequencing of mucosal melanomas reveals that they are driven by distinct mechanisms from cutaneous melanoma. J Pathol 2013;230:261-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hou JY, Baptiste C, Hombalegowda RB, et al. Vulvar and vaginal melanoma: A unique subclass of mucosal melanoma based on a comprehensive molecular analysis of 51 cases compared with 2253 cases of nongynecologic melanoma. Cancer 2017;123:1333-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell 2015;161:1681-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the braf gene in human cancer. Nature 2002;417:949-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edwards RH, Ward MR, Wu H, et al. Absence of braf mutations in uv-protected mucosal melanomas. J Med Genet 2004;41:270-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khalil DN, Carvajal RD. Treatments for noncutaneous melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2014;28:507-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saglam O, Naqvi SMH, Zhang Y, et al. Female genitourinary tract melanoma: Mutation analysis with clinicopathologic correlation: A single-institution experience. Melanoma Res 2018;28:586-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Omholt K, Grafstrom E, Kanter-Lewensohn L, et al. Kit pathway alterations in mucosal melanomas of the vulva and other sites. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:3933-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oxley JD, Corbishley C, Down L, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular study of penile melanoma. J Clin Pathol 2012;65:228-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papeš D, Altarac S, Arslani N, et al. Melanoma of the glans penis and urethra. Urology 2014;83:6-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okazaki T, Chikuma S, Iwai Y, et al. A rheostat for immune responses: The unique properties of pd-1 and their advantages for clinical application. Nat Immunol 2013;14:1212-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaunitz GJ, Cottrell TR, Lilo M, et al. Melanoma subtypes demonstrate distinct pd-l1 expression profiles. Lab Invest 2017;97:1063-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rambhia PH, Scott JF, Vyas R, et al. Genitourinary melanoma. In: Scott JF, Gerstenblith MR. editors. Noncutaneous melanoma. Brisbane (AU) (2018).

- McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, et al. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer 2005;103:1000-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vyas R, Thompson CL, Zargar H, et al. Epidemiology of genitourinary melanoma in the united states: 1992 through 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;75:144-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsao H, Chin L, Garraway LA, et al. Melanoma: From mutations to medicine. Genes Dev 2012;26:1131-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cazenave H, Maubec E, Mohamdi H, et al. Genital and anorectal mucosal melanoma is associated with cutaneous melanoma in patients and in families. Br J Dermatol 2013;169:594-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanchez A, Rodríguez D, Allard CB, et al. Primary genitourinary melanoma: Epidemiology and disease-specific survival in a large population-based cohort. Urol Oncol 2016;34:166.e7-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rogers T, Pulitzer M, Marino ML, et al. Early diagnosis of genital mucosal melanoma: How good are our dermoscopic criteria? Dermatol Pract Concept 2016;6:43-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karasawa K, Wakatsuki M, Kato S, et al. Clinical trial of carbon ion radiotherapy for gynecological melanoma. J Radiat Res 2014;55:343-350. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ragnarsson-Olding BK, Kanter-Lewensohn LR, Lagerlof B, et al. Malignant melanoma of the vulva in a nationwide, 25-year study of 219 swedish females: Clinical observations and histopathologic features. Cancer 1999;86:1273-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferreira DM, Bezerra ROF, Ortega CD, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the vagina: An overview for radiologists with emphasis on clinical decision making. Radiol Bras 2015;48:249-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noguchi T, Ota N, Mabuchi Y, et al. A case of malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix with disseminated metastases throughout the vaginal wall. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2017;2017:5656340 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gökaslan H, Sismanoglu A, Pekin T, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the vagina: A case report and review of the current treatment options. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005;121:243-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moxley KM, Fader AN, Rose PG, et al. Malignant melanoma of the vulva: An extension of cutaneous melanoma? Gynecol Oncol 2011;122:612-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frumovitz M, Etchepareborda M, Sun CC, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1358-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baraziol R, Schiavon M, Fraccalanza E, et al. Melanoma in situ of penis: A very rare entity: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine 2017;96:e7652 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jabiles AG, Del Mar EY, Perez GAD, et al. Penile melanoma: A 20-year analysis of six patients at the national cancer institute of peru, lima. Ecancermedicalscience 2017;11:731. [PubMed]

- van Geel AN, den Bakker MA, Kirkels W, et al. Prognosis of primary mucosal penile melanoma: A series of 19 dutch patients and 47 patients from the literature. Urology 2007;70:143-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ortiz R, Huang SF, Tamboli P, et al. Melanoma of the penis, scrotum and male urethra: A 40-year single institution experience. J Urol 2005;173:1958-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stillwell TJ, Zincke H, Gaffey TA, et al. Malignant melanoma of the penis. J Urol 1988;140:72-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Safadi S, Estel R, Mayser P, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the urethra: A systematic analysis of the current literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289:935-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Venyo AK. Melanoma of the urinary bladder: A review of the literature. Surg Res Pract 2014;2014:605802 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bumbu GA, Berechet MC, Pop OL, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the bladder - case report and literature overview. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2019;60:287-92. [PubMed]

- Khan M, O'Kane D, Du Plessis J, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder and ureter. Can J Urol 2016;23:8171-5. [PubMed]

- Kirigin M, Lez C, Sarcevic B, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder: Case report. Acta Clin Croat 2019;58:180-2. [PubMed]

- Barillaro F, Camilli M, Dessanti P, et al. Primary melanoma of the bladder: Case report and review of the literature. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2018;90:224-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buscarini M, Conforti C, Incalzi RA, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the bladder. Skinmed 2017;15:395-7. [PubMed]

- Meunier R, Pareek G, Amin A. Metastasis of malignant melanoma to urinary bladder: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Pathol 2015;2015:173870 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth AM, Clark WH, Mastrangelo M, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder. Cancer 1976;37:1928-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liapis G, Sarlanis H, Poulaki E, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of renal pelvis with extensive clear cell change. Cureus 2016;8:e583 [PubMed]

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the american joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:472-92.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: A multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:296-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janco JM, Markovic SN, Weaver AL, et al. Vulvar and vaginal melanoma: Case series and review of current management options including neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 2013;129:533-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doepker MP, Zager JS. Sentinel lymph node mapping in melanoma in the twenty-first century. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2015;24:249-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan P, Curry JL, Ning J, et al. Tumor thickness and mitotic rate robustly predict melanoma-specific survival in patients with primary vulvar melanoma: A retrospective review of 100 cases. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2093-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seifried S, Haydu LE, Quinn MJ, et al. Melanoma of the vulva and vagina: Principles of staging and their relevance to management based on a clinicopathologic analysis of 85 cases. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:1959-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piura B. Management of primary melanoma of the female urogenital tract. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:973-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia L, Han D, Yang W, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the vagina: A retrospective clinicopathologic study of 44 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014;24:149-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phillips GL, Bundy BN, Okagaki T, et al. Malignant melanoma of the vulva treated by radical hemivulvectomy. A prospective study of the gynecologic oncology group. Cancer 1994;73:2626-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kottschade LA, Grotz TE, Dronca RS, et al. Rare presentations of primary melanoma and special populations: A systematic review. Am J Clin Oncol 2014;37:635-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rema P, Suchetha S, Ahmed I. Primary malignant melanoma of vagina treated by total pelvic exenteration. Indian J Surg 2016;78:65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papeš D, Altarac S. Melanoma of the female urethra. Med Oncol 2013;30:329. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dhar KK, Das N, Brinkman DA, et al. Utility of sentinel node biopsy in vulvar and vaginal melanoma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2007;17:720-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abramova L, Parekh J, Irvin WP Jr, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in vulvar and vaginal melanoma: Presentation of six cases and a literature review. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9:840-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krengli M, Masini L, Kaanders JHAM, et al. Radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: Analysis of 74 cases. A rare cancer network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:751-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pow-Sang JM, Klimberg IW, Hackett RL, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the male urethra. J Urol 1988;139:1304-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dimarco DS, Dimarco CS, Zincke H, et al. Surgical treatment for local control of female urethral carcinoma. Urol Oncol 2004;22:404-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine RL. Urethral cancer. Cancer 1980;45:1965-72. [Crossref]

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Kapp DS. Management of melanomas of the female genital tract. Curr Opin Oncol 2008;20:565-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stein BS, Kendall AR. Malignant melanoma of the genitourinary tract. J Urol 1984;132:859-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bracken RB, Diokno AC. Melanoma of the penis and the urethra: 2 case reports and review of the literature. J Urol 1974;111:198-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bittar JM, Bittar PG, Wan MT, et al. Systematic review of surgical treatment and outcomes after local surgery of primary cutaneous melanomas of the penis and scrotum. Dermatol Surg 2018;44:1159-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wollina U, Steinbach F, Verma S, et al. Penile tumours: A review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28:1267-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bechara GR, Schwindt AB, Ornellas AA, et al. Penile primary melanoma: Analysis of 6 patients treated at brazilian national cancer institute in the last eight years. Int Braz J Urol 2013;39:823-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the american joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:472-92.

- Nguyen AT, Kavolius JP, Russo P, et al. Primary genitourinary melanoma. Urology 2001;57:633-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watanabe J, Yamamoto S, Souma T, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the male urethra. Int J Urol 2000;7:351-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wood HM, Angermeier KW. Anatomic considerations of the penis, lymphatic drainage, and biopsy of the sentinel node. Urol Clin North Am 2010;37:327-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hankins CL, Weston P. Re: Melanoma of the penis, scrotum and male urethra: A 40-year single institution experience: R. Sánchez-ortiz, sf huang, p. Tamboli, vc prieto, g. Hester and ca pettaway. J Urol 2006;175:1574-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- García Montes F, Lorenzo Gomez MF, Boyd J. does primary melanoma of the bladder exist? Actas Urol Esp 2000;24:433-6. [PubMed]

- Van Ahlen H, Nicolas V, Lenz W, et al. Primary melanoma of urinary bladder. Urology 1992;40:550-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Ammari JE, Ahallal Y, El Fassi MJ, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder. Case Rep Urol 2011;2011:932973 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gakis G, Merseburger AS, Sotlar K, et al. Metastasis of malignant melanoma in the ureter: Possible algorithms for a therapeutic approach. Int J Urol 2009;16:407-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Macneil J, Hossack T. A case of metastatic melanoma in the ureter. Case Rep Urol 2016;2016:1853015 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shoushtari AN, Munhoz RR, Kuk D, et al. The efficacy of anti-pd-1 agents in acral and mucosal melanoma. Cancer 2016;122:3354-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Angelo SP, Larkin J, Sosman JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab in patients with mucosal melanoma: A pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:226-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yi JH, Yi SY, Lee HR, et al. Dacarbazine-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment in noncutaneous metastatic melanoma: Multicenter, retrospective analysis in asia. Melanoma Research 2011;21:223-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lian B, Si L, Cui C, et al. Phase ii randomized trial comparing high-dose ifn-α2b with temozolomide plus cisplatin as systemic adjuvant therapy for resected mucosal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4488-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim KB, Sanguino AM, Hodges C, et al. Biochemotherapy in patients with metastatic anorectal mucosal melanoma. Cancer 2004;100:1478-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harting MS, Kim KB. Biochemotherapy in patients with advanced vulvovaginal mucosal melanoma. Melanoma Research 2004;14:517-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD, et al. Kit as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA 2011;305:2327-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, et al. Phase ii, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2904-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified kit arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3182-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Postow MA, Luke JJ, Bluth MJ, et al. Ipilimumab for patients with advanced mucosal melanoma. Oncologist 2013;18:726-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo J, Carvajal RD, Dummer R, et al. Efficacy and safety of nilotinib in patients with kit-mutated metastatic or inoperable melanoma: Final results from the global, single-arm, phase ii team trial. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1380-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ipilimumab and nivolumab as adjuvant treatment of mucosal melanoma. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03241186?cond=mucosal+melanoma&rank=5

- Apatinib plus shr1210 in advanced mucosal melanoma. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03986515?cond=mucosal+melanoma&rank=7

- Plx3397 kit in acral and mucosal melanoma (piano). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02071940?cond=mucosal+melanoma&rank=9

Cite this article as: Carr MJ, Sun J, Spiess PE, Zager JS. Advances in the management of genitourinary melanomas. AME Med J 2019;4:41.